Pre-Battle Context

Prior to the outbreak of hostilities, the Nigerian Navy was tasked with enforcing a blockade around Port Harcourt and the Bonny River. By October 1967, the capture of Calabar and other coastal cities had left Port Harcourt’s airport as Biafra’s sole means of international communication and travel. The Biafrans responded by constructing makeshift airstrips from old roadways. Initially, Port Harcourt was lightly defended, but its fortifications were reinforced following the capture of Bonny by federal forces. To obstruct a federal advance, the Biafrans scuttled a barge and dumped several vehicles into the river.

Battle for Port Harcourt

Following their defeat in the Cross River region, the Biafrans reorganized and established the 12th Division under Lt. Col. Festus Akagha. This division comprised the 56th Brigade, stationed in Arochukwu, and the 58th Brigade, stationed in Uyo. On March 8, 1968, Nigerian forces launched a heavy aerial and naval bombardment on the beaches at Oron. The Nigerian 33rd Brigade, led by Col. Ted Hamman, swiftly overran Biafran defensive positions and advanced towards Uyo. The rapid Nigerian advance caused disarray among Biafran officers, leading to the surrender of numerous Biafran troops as the Nigerian 16th and 17th Brigades, commanded by Col. E.A. Etuk and Lt. Col. Philemon Shande respectively, stormed through Eket and occupied Opobo.

With Biafran forces in retreat, the Nigerian 15th Brigade, under Col. Ipoola Alani Akinrinade, launched an attack on Port Harcourt, which was then defended by the Biafran 52nd Brigade led by Col. Ogbugo Kalu. Despite intense fighting, Nigerian troops captured Onne and established a position there, though their success was short-lived. A counter-attack by Biafran forces, including an Italian-born mercenary, inflicted heavy casualties on the Nigerians and forced them to retreat from Onne. Additionally, the Biafran 14th Battalion stationed in Bori panicked and withdrew upon seeing Nigerian soldiers in 14th Brigade insignia.

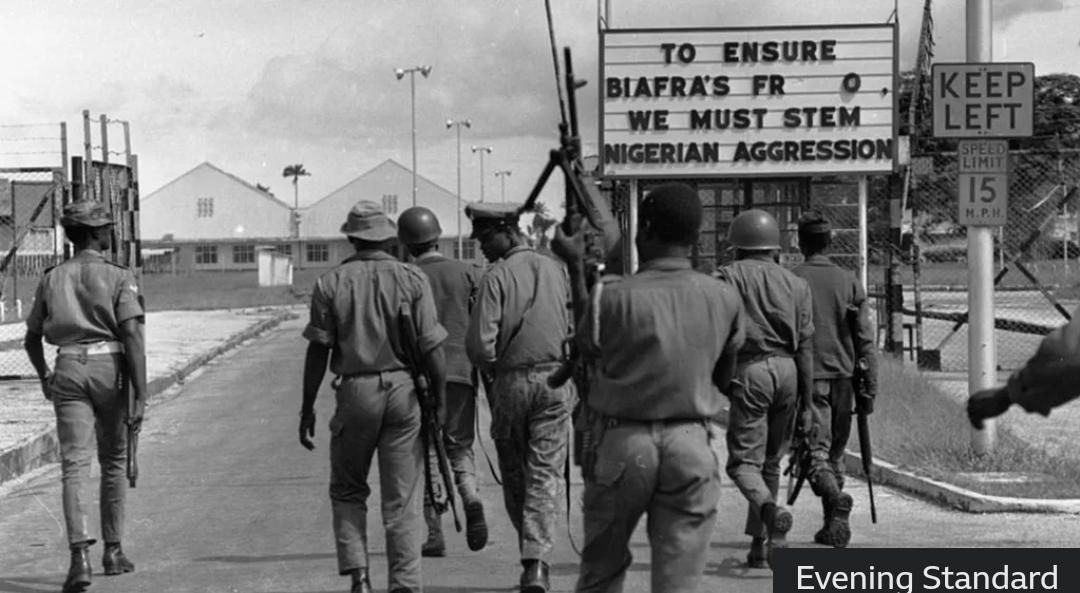

As Biafran defenses around Port Harcourt crumbled, Radio Biafra called for the city’s defense. On May 19, Biafran Maj. Joseph Achuzie arrived in Port Harcourt and took command of the defending troops. Despite a relentless Nigerian artillery bombardment, Biafran forces fiercely resisted. For five days, control of the airport and army barracks shifted multiple times, but by May 24, most Biafran troops had been pushed out of the city. Maj. Achuzie narrowly escaped death after an armored car nearly ran him over, and eventually retreated to Igrita.

Aftermath

The capture of Port Harcourt by Nigerian forces effectively cut off Biafra’s access to the sea. Nigerian authorities viewed it as a crucial victory, with President Gowon noting that Biafra might have achieved international recognition if it had held the port for another month. The Nigerians also gained control of the city’s airport, which became a forward base for air raids into Biafra’s interior. The day after Port Harcourt’s capture, Gen. Adekunle famously announced that he would capture Owerri, Aba, and Umuahia within two weeks. However, Nigerian forces did not capture Owerri and Aba until October 1, 1968, and Umuahia remained out of reach until the following year. On January 15, 1970, Biafra officially surrendered, ending the war.

The fall of Port Harcourt led to a large-scale exodus of the Igbo population, who fled into Biafra’s interior, leaving behind their homes and belongings. Those who remained were either killed or displaced. Many Ijaw people welcomed the federal troops, claiming abandoned properties and assuming local leadership roles. After the war, the returning Igbos, many of whom were needed for managing the oil industry, were housed in protected areas and the government guaranteed their safety. However, the process of reclaiming abandoned properties in Port Harcourt was fraught with difficulties, as the Rivers State government resisted federal directives to evict squatters. State courts often sided with the squatters, leading to perceptions among Igbo owners of a state policy of retribution.