Lt. Col. Victor Adebukunola Banjo stands as one of the few notable Yoruba soldiers who fought for the Biafran Army during Nigeria’s Civil War, a conflict that lasted from 1967 to 1970. His role in the war, particularly his near-capture of Lagos in 1967 for the Biafran forces, remains a significant part of his legacy. However, his failure in the mission ultimately led to his execution. Banjo’s story challenges simplistic narratives of the war being solely a genocidal conflict between ethnic groups, as his commitment to the Biafran cause shows that the war had more complex motivations, including those of national unity and opposition to tribalism.

Some have argued that the Nigerian Civil War was not a mere civil war but a genocidal conflict between the Biafrans and a coalition of Yoruba, Hausa, and Fulani groups, with support from global powers like Great Britain, Russia, and the United States. However, this view often overlooks figures like Banjo, a Yoruba man who defied ethnic loyalties to fight on the side of the Biafran Army, believing in the cause until his execution in 1967.

Early Life and Military Career

Victor Adebukunola Banjo was born on April 1, 1930, in the Ijebu area of Ogun State, southwestern Nigeria. Not much is known about his early life, but by 1953, Banjo had joined the Nigerian Army as a Warrant Officer, a role that would eventually lead him to become a key figure in the military history of Nigeria. He was part of a generation of young, ambitious officers rising through the ranks of the Nigerian military.

In 1956, Banjo became the 16th Nigerian officer to be commissioned in the Nigerian Army (NA 16), a notable accomplishment for the time. The colonial military system allowed Nigerian officers access to advanced military training overseas, and Banjo benefited from this. He was sent to the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in England, where he completed his military education. In addition to his military training, Banjo also earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Mechanical Engineering, making him not just a soldier but also a technically skilled officer.

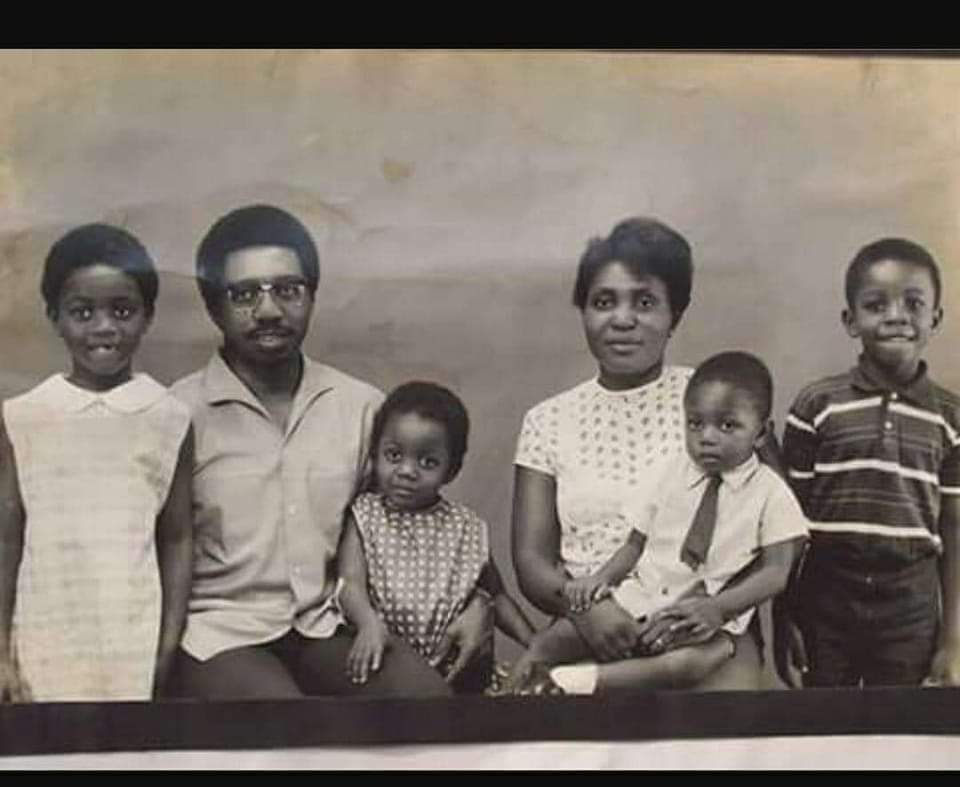

By the early 1960s, Banjo had risen to prominence within the Nigerian military, becoming the first Nigerian Director of the Electrical and Mechanical Engineering Corps of the Nigerian Army. He was seen as a promising officer, with a bright future ahead of him. At this point in his life, Banjo was in his 30s, married with two children, and leading what could be described as an ideal military career.

The 1966 Coup and Detention

Banjo’s military career took a dramatic turn on January 15, 1966, when a group of young officers staged a coup d’état, toppling the civilian government of Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa. The coup resulted in the deaths of many key political figures, including national and regional leaders. This event is often referred to as the 1966 coup and is one of the most pivotal moments in Nigeria’s history. While Banjo did not directly participate in the coup, its aftermath significantly affected his life and career.

After Major-General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi assumed power following the coup, Banjo was summoned to meet with the newly-appointed Supreme Military Commander. While waiting to see Ironsi, Banjo was unexpectedly arrested. The reasons for his arrest were unclear, but he was accused of plotting to assassinate General Aguiyi-Ironsi, a charge for which there was little to no evidence. Banjo was detained without trial, becoming a political scapegoat in the turbulent aftermath of the coup.

The 1966 coup had been widely regarded as ethnically motivated, as the majority of the coup leaders were Igbo, and many of the victims were from the northern regions of Nigeria. Ironsi, who hailed from the Igbo-speaking part of Delta State, faced immense pressure from the northern military officers and civilians to punish those responsible for the coup. As tensions rose, tribal divisions became more pronounced. Banjo, a Yoruba officer, was caught in this web of ethnic politics and was detained without any formal charges or trial.

Banjo remained in prison for several months. During this period, he protested his innocence and tried to defend a fellow Yoruba soldier who had been similarly detained. His attempt to stand up for his colleague only led to his further incarceration. He remained imprisoned until May 1967, when his life took another dramatic turn.

Letters from Prison

Banjo’s time in prison revealed much about his character and his worldview. Despite his difficult circumstances, he maintained close contact with his family through constant letter writing. According to the book A Gift of Sequins, Banjo, who by then had four children, used his letters to stay connected with his loved ones and to offer support during what was undoubtedly a hard time for them.

These letters provide insight into Banjo’s liberal, non-tribalistic outlook. He saw himself not merely as a Yoruba man but as a Nigerian who wanted to see his country move beyond ethnic divisions. His letters showed that he believed in the potential of Nigeria as a united nation and wanted to see his fellow soldiers and countrymen rise above tribalism to build a stronger, more inclusive society.

Joining the Biafran Army

When the Nigerian Civil War broke out in July 1967, Banjo was still imprisoned, but now in the eastern part of the country. Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, the leader of the secessionist Biafran nation, saw potential in Banjo and decided to release him from prison. Ojukwu promoted Banjo to the rank of Colonel in the Biafran Army, despite his Yoruba heritage, and tasked him with leading military operations against the Nigerian government.

Banjo’s decision to fight for Biafra was not merely a matter of loyalty to Ojukwu. He believed that Nigeria was plagued by institutional tribalism and saw the Biafran cause as an opportunity to fight against what he viewed as systemic injustice. Banjo’s motivations were rooted in his desire to rid Nigeria of tribalism and build a fairer society.

In his own words, Banjo later explained, “However, when I discovered the emerging trend that followed the declaration of independence of Biafra, it became clear to me that a war with the North was imminent. I decided to stay behind and assist in the prosecution of the war, both for the sake of my friendship with Colonel Ojukwu and in the hope that, having assisted to fight back the Northern threat to Biafra, he would assist me with troops to rid the Mid-West and Lagos of the same menace.”

The Offensive and Retreat

Banjo quickly proved himself as a skilled tactician and fearless soldier in the Biafran Army. When the Nigerian Army launched its invasion of Biafra on July 6, 1967, Ojukwu sent Banjo, along with Major Albert Okonkwo and Major Emmanuel Ifeajuna, to lead an offensive into Nigeria. Banjo’s forces advanced rapidly, capturing Benin City in less than 24 hours. Within a short time, his division had moved within 300 kilometers of Lagos, Nigeria’s capital.

However, something changed during the final stages of the offensive. As Banjo’s forces approached Lagos, they unexpectedly halted their advance and retreated back to Biafra. The reasons for this sudden retreat remain unclear. Some speculate that Banjo and his fellow commanders, particularly Ifeajuna, did not fully support the idea of breaking up Nigeria and may have had second thoughts about the Biafran cause.

Ojukwu, however, viewed the retreat as an act of betrayal and sabotage. He accused Banjo, Okonkwo, and Ifeajuna of conspiring against Biafra and ordered their arrest.

Trial and Execution

Banjo and the other commanders were put on trial for conspiracy against the Biafran state. The first tribunal dismissed the case, but a second tribunal found them guilty and sentenced them to death. At his sentencing, Banjo remained defiant. He proclaimed, “I came into the war at a moment of temporary collapse of the Biafran fighting effort, when it became quite clear to me that the fighting effort of the Biafran Army was not only being incompetently handled, but also being sabotaged.”

On September 22, 1967, Banjo, along with Emmanuel Ifeajuna and Philip Alale, was executed by firing squad in the city center of Enugu. As Banjo was hit by the first round of bullets, he reportedly shouted, “I’m not dead yet!” and had to be shot multiple times before he finally succumbed.

Legacy

Today, the story of Lt. Col. Victor Banjo is largely forgotten, overshadowed by the larger narratives of the Nigerian Civil War. However, his legacy remains significant as a symbol of the complexities of Nigeria’s ethnic and political landscape. In a country still deeply divided along tribal lines, Banjo’s life stands as a testament to the possibility of transcending ethnic loyalties for a greater cause. His decision to fight for Biafra, despite being a Yoruba man, and his ultimate sacrifice for his beliefs, highlight the depth of his commitment to his ideals and his vision for a more just and united Nigeria.